Author David Hill on the things we leave behind.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand

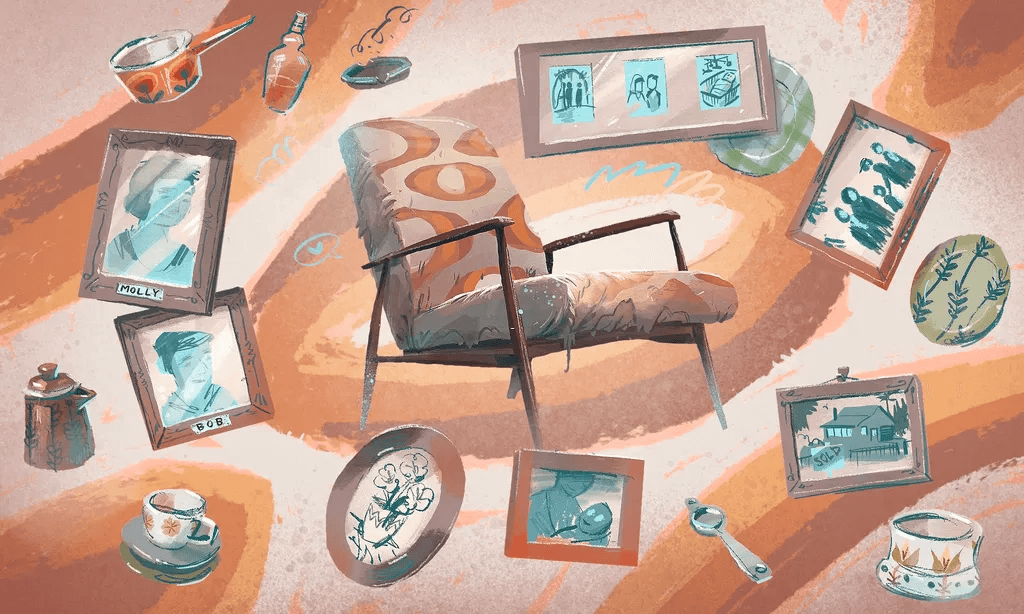

Original illustrations by Gavin Mouldey

After my mother was buried, my father raged through the house, throwing out or giving away her possessions. I came home from university to find the wardrobe half-emptied, bare spaces on table and mantelpiece where she used to keep her ashtrays.

Those ashtrays were probably too savage a reminder of the emphysema that killed her in her early 50s. Other things went because of…. my dad’s grief at the reminders they held? His anger, since all the bereaved feel anger at some stage? His sudden explosions of physical restlessness, and his need to be doing something, anything? All those, I guess.

Yet he didn’t toss out her armchair.

My mother’s armchair wasn’t much to look at. They bought it secondhand, soon after we moved to the first house they ever owned. They’d spent years saving for that golden, post-WW2 vision, A Place Of Their Own. Furniture and fittings could wait till they had a home to put such things in.

“Armchair” is hyperbole. It did have arms: skinny wooden ones in cheap dark varnish. Seat and back in meagre brown fabric. Legs as minimal and unaesthetic as the arms. But I presume it was comfortable for her back, already painful as the lung cancer began to invade.

So why did my father keep it?

Did he want to punish, torment himself somehow? Did he picture Mum sitting in it, as she did for much of her last year? Surely not. She was a distressing sight during those months: skeletal and yellow-skinned, hunching forward as she laboured to breathe.

Yet six decades later, I can believe that’s one reason for his holding on to that tatty bit of furniture. I’ve tried to exorcise my mother’s death by writing about it. I can visualise my father staring at that chair through his evenings alone when I was back at university – while also writing her dying over and over in his head.

And if sometimes she became for him the young, healthy woman I knew only from a few blurry Box Brownie photos, I can relate to that as well. I’ve tried to record that person, too.

My dad lived 11 years as a widower. He must have been lonely, especially when I was away at university in Wellington and then teachers’ college in Auckland. I know he had to get up suddenly, barge out and drive to the Taradale shops, walk around where other people were. A neighbour told me about it; I think she’d felt affronted when he strode off partway through a conversation.

So I worried about him intermittently, but since he was only my father, I didn’t take all that much notice.

When I was home, he and I were more relaxed, more expansive with each other than we’d been for years. We argued – over trade unionism (him in favour; me against), and finances (saving for him; spending for me). “Y’can’t tell me…” he’d declaim. And indeed, I couldn’t.

But mostly, after Mum’s ugly death, we wanted peace. The house was calmer without her. Calmer and less vital. We could start constructing a happier, selective narrative of her.

Together we were two placid bachelors, fussed over by women in the neighbourhood. We kept the place tidy, if unscrubbed or unwiped in places we never thought of.

He looked after himself well enough, though the same neighbour tutted about his cooking habits. Apparently he’d cook a stew on Sunday, then leave it on the stove and reheat it on Monday/Tuesday/Wednesday.

“I just about turned green when I realised!” my informant gasped. “Like the stew?” I suggested, which wasn’t very responsible of me.

At home in the long summer holidays, working in Napier’s De Pelichet McLeod woolstore where he spent 30-plus years, I realised he was seen as the top wool-classer, deferred to by others. How could he be top at anything? He was only my father, remember.

He enjoyed language. It took me too long to understand this, but in the three years between Mum dying and my wife Beth arriving in my life, I came to appreciate his demotic phrasings. A local actress of some notoriety was “tough as old goats’ knees”. A parsimonious neighbour was “tight as a bull going up a steep cliff”. I’ve been able to use both of those.

Over those 11 years, he became reconciled, even contented. He built a modest social life. He was delighted when I married Beth.

On the morning of our wedding, when I dropped in to the New Plymouth hotel where all the waitresses thought he was a dear old bloke, he went: “I’m sorry your mother couldn’t be here to see you so happy, son.” Then he grinned, patted me on the shoulder, said, “I’ll make up for it, don’t worry.”

A bit further on, and he turned into a near-caricature of the doting grandparent. “Isn’t he a great little bloke?” he’d exult about Pete. “Isn’t he?” Everyone humoured him.

Mum’s armchair meanwhile stayed in a corner of the living room. He never used it; didn’t mind if someone else did. Maybe he came to feel that getting rid of it would be a betrayal, a renunciation. In the rawness of his grief, he’d thrown out so many of Mum’s things that he wasn’t going to do the same with what remained.

And maybe (I’m fantasising here, but I’ve become so like him that it’s a fantasy supported by evidence) he could rest his hand on the chair, talk to it, imagine he was doing the same to my mother.

When he died, wonderfully and painlessly in his sleep, I drove down through the night to Taradale, let myself into the house, stood with my own hand on the back of Mum’s chair; listened to the silence around.

I lit a fire, found the brandy in the biscuit cupboard and sat beside the flames, feeling relief. I’d made it, and so had my father. He’d have been pleased to finish so tidily, to make so little trouble.

I raised the glass, said “Cheers, Bob Hill”, heard my voice crack. There was too much brandy left and I needed to get some sleep, so I tossed it on the fire. A spray of blue flame flared across the room. I leaped sideways, yelling, “Shit!” He’d have liked that.

Then for the two days before his funeral, and before Beth and Pete could fly down, I watched myself imitate my father.

I strode from room to room, taking crockery, bedding, kitchenware, piling it on the back lawn for dump or hospice shop. I wasn’t raging like Dad. I was calm with exhaustion and with gratitude for his peaceful end. Yet I needed to cleanse the place, mark a change. I wasn’t a son any longer; never would be again. Suddenly, I was the oldest in our family. My father’s order had to give way, and his house was the place to start.

The armchair went out, too. But I didn’t toss it on the grass like other stuff. I sat in it for a few minutes, very consciously. Then I carried it out, placed it to one side of the growing pile.

I’d known in advance I wouldn’t keep it. It was unfashionable, unattractive, even unhygienic. It would have meant pressure on Beth, trying to find a place where it wasn’t either hidden away or incongruous.

I don’t believe property is necessarily theft, as Proudhon claimed. But it can be a burden, an imposition on later generations. I didn’t feel I was casting my mother aside when I put out her chair, any more than Dad was in his anguished purging of her belongings.

I kept a small silver tea-stand I’d given my parents for their 25th wedding anniversary; a couple of pieces of china. Decades on, do I regret not having more mementoes of them?

In fact, I have many. They’re intangible but insistent, as present and more immediate than any physical object.

I hear the way my mother went “Oh?” and lifted her head when she was uncertain. I see my father’s splay-footed, loose-legged walk, his distress at arguments or confrontations.

I see and hear them most in the stories I’ve written where their lives and deaths appear in multiple guises. That’ll do me for mementoes.

Current wisdom says we die three times: final breath; burial/cremation; when someone says or sees our name for the last time. If writing about my parents has delayed their final death at all, I’ll be happy.

The Sunday Essay postcard set is now available from The Spinoff shop. The set features 10 original illustrations from the series.