Charlotte Graham-McLay is dazzled by the new novel by JK Rowling (writing as Robert Galbraith), which arrived in shops this week and went flying out the door like broomsticks.

Crime writers have long specialised in grotesquely, even comically bad men, but if there’s one thing the past year has taught us, it’s that we aren’t always sure what a bad man looks like anymore, and we’re worse at spotting them than we supposed. In his ambitious new book, Lethal White – the fourth in a bestselling detective series featuring a dour private eye and his kind, clever business partner – British writer Robert Galbraith jabs and pokes at our ideas of bad men like a tongue at a loose tooth.

“Was pulling a phone out of her hand any worse than deleting her call history?” one character wonders about the man she has stood by despite escalating red flags; not the stabby, chopping women into pieces kind of red flags, just the slow erosion of dignity kind. Where, she asks herself, is her “red line?”

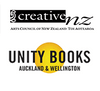

Of course, it’s silly to keep calling the writer Robert Galbraith, a pen name for JK Rowling; famous for the Harry Potter books and her every Twitter pronouncement. She tried to keep Galbraith’s identity a secret when she published the first book in the Strike series, The Cuckoo’s Calling, back in 2013. The secrecy held for about five minutes. (Being famous is not well-reviewed in this book; its detective hero, Cormoran Strike, complains of becoming “a sensational oddity, a jokey aside on quiz shows.”)

It feels wrong not to credit Rowling straight away with this novel, because for all its occasional flaws and frustrations, the series, and the most recent two books in particular, are among her most exciting works in ages, and surely stand up with Potter as her best. After immersing myself for a few days in Lethal White’s 650-odd pages (too many, but more on that later), the thought that I would likely have to wait years for more in the series sort of broke my heart. Poor Rowling, in hock forever to Warner Brothers, is busy writing screenplays for her film series Fantastic Beasts – set in the Harry Potter universe, and redolent of movie studio excess and the scenery chewing of glazed Christmas ham Johnny Depp. She still has at least three films left to write, and the Strike novels are where I wish she could spend her time instead.

In this latest instalment, Strike, a disabled Afghan war veteran with an unlucky history in family and ex-girlfriends, is approached by a man in the throes of a mental breakdown, who claims he witnessed a child being strangled to death when he was small. When Strike catches another case in the halls of Westminster, he’s forced to try to work out whether the two stories are linked. The sprawling, complicated hunt for a killer spans family, politicians, wealthy landed gentry and the middle-class activists of London, and unfolds against the backdrop of preparations for the 2012 Olympics. Alongside Strike is his once-assistant, now business partner, Robin Ellacott; as well as proving instrumental in solving the case, Robin’s wrestling with her demons and anguish over whether her marriage was supposed to last form the moral centre of the book.

Few things are more delicious in literature than a thoroughly gruesome wedding, and at the start of Lethal White, Rowling plays an absolute blinder: the happy couple begin fighting immediately after the ceremony and the bride has recently been stabbed. Rowling has always been a total savage in skewering people she finds awful (yes, even in the children’s books that made her famous), a list that in this novel extends to rich people, social justice warriors, all exes everywhere, and large swathes of men.

She doesn’t appear to be a fan of weddings or much of Twitter. One activist’s timeline is “a strange mix of the cloying and the vituperative,” Rowling writes. “‘I hope you get fucking arse cancer, you Tory cunt,’ sat directly above a video clip of a kitten sneezing so hard that it fell out of its basket.’”

Strike, the private eye detective and purportedly the series’ main character, is a guest at the wedding that opens the book, but Rowling seems to have realised it’s his assistant Robin, the ill-fated bride, that fans are really here for. Strike, a former military police officer who’s still coming to terms with amputation of one leg after an explosion in Afghanistan, is a good character; sometimes even excellent. He does the brooding loner traversing London to solve crimes thing with humour and skill, but with an essential humanity, and genuine care for Robin, that prevents him from being merely a Sherlock Holmes cipher.

But his interior life, by the fourth book of the series, pales in comparison to that of his assistant, who’s proven to be its star. Midway through the previous Galbraith book, Career of Evil, Rowling started to write in a ferocious sort of way that made you sit up, say, “Oh, OK then!” and commit to the series with renewed interest.

There had always been a pall over Rowling’s Robin; a nice, intelligent girl who somehow found herself drawn into Strike’s seedy, criminal London, and appeared inexplicably trapped in a frustrating relationship with a fiancé who didn’t seem to respect her at all. She seemed out of place. And then Rowling, in finally addressing Robin’s story of dropping out of university years earlier, filled in the blanks: she’d returned home from uni afteran horrific sexual assault, and had never been back. The awful boyfriend? The last relic of a terrible time when she needed someone and he had been there for her. The job chasing criminals with Strike suddenly made sense too.

My copy of Career of Evil, when I opened it recently, was full of furious highlights, even though I’d only read it for fun: “Robin felt as though she were fighting all over again for the identities she had been forced to relinquish the last time a man had lunged at her out of the darkness,” Rowling wrote, and later: “She was no longer the person who had lain on her bed staring at Destiny’s Child. She refused to be that girl.”

And so, like watching Usain Bolt suddenly pull out an Olympic gymnastics tumbling pass, Rowling’s Galbraith went from a rich writer having a fun time mucking around with something new, to an author on the very short list of those who get it, get it, get it.

The best part of Lethal White is watching her refuse to squander Robin. Recently, at the Christchurch Writers Festival, I spoke to Denise Mina – another of the writers on that short list – about her bracing character Maureen O’Donnell from the Garnethill trilogy, a woman fighting back after childhood sexual abuse, who finds a way to live with what she’s got. Mina said her publishers had put pressure on her to see Maureen transcend her pain to become an action hero in the later books, but she refused because life isn’t like that. When Maureen’s recovery was shaky and piecemeal, instead of triumphant, the second two books in the trilogy didn’t sell well, but those of us who bought them got it, and Mina had us for life.

Similarly, Rowling has Robin survive a serial killer on her own wits at the end of the third Strike novel, but in Lethal White, the character struggles with panic attacks and fear that her beloved job will be at risk if she talks about them. “So she stood motionless, palms pressed against the partition walls, speaking to herself inside her head as though she were an animal handler, and her body, in its irrational terror, a frantic prey creature,” Rowling writes of Robin, locked in a toilet cubicle.

She isn’t finished with Robin’s journey yet, or Strike’s – his parallel is the amputated leg that he refuses to accommodate, rushing around London on foot until he collapses or his stump is rubbed raw – and the ratcheting sexual tension between the two of them is a grenade ready to explode. The pair are workmates, plus Robin has only ever had one boyfriend and he’s an idiot. Robin and Strike seem fated to get together and it seems fated to also be really terrible and I can’t wait.

It isn’t a perfect book. For a start, Rowling’s descriptions of settings drag, especially when they’re real places, like Westminster, that we can imagine perfectly well on our own. “Stop world-building!” I wanted to yell. “You’re not at Hogwarts now!” In the acknowledgements, Rowling thanks famous friends and MPs for getting her access to various locales, but she didn’t need to show us all the working.

While the writing is Rowling’s signature, simple blend of straightforward narrative and wry wit, her sentences are often overstuffed with clauses and unnecessary punctuation. This began to happen towards the end of the Potter series, which suggests to me that you can eventually become famous enough that people don’t make you do edits anymore. What a life! And as is usual for Rowling, the action begins too late in the book, although at least in this one, we’ve got tantalising clues to start unravelling, so it’s not too much of a burden – unlike her other adult novel, The Casual Vacancy, in which the utter lack of action for the first 80% of the book meant many readers had given up before reaching the brilliance of the last hundred pages.

But I trust Rowling with this story because characters have always been the best of her; we came to Potter for the spells and the food, but stayed for her direct line into the human condition. This series is no different. If anything, she could be bolder with the next book, less inclined to paint characters in black and white. If a novelist has ever written pettier, mean-spirited characters in unsalvageable relationships, I struggle to think of them! But the lovely Robin’s fiancé, Matthew, is at his most loathsome, and authentic, when he’s snidely undermining her job and her friends; there’s no need, as Rowling does, to throw in a bigger sin to convince us of how much we should dislike him. She should trust that we follow: there are degrees of bad people and it’s possible to hurt, and to overcome, in many different ways. And a good edit wouldn’t hurt.

The Spinoff Review of Books is brought to you by Unity Books.