The poet Hera Lindsay Bird interviews the brilliant American writer Mark Leidner, and does her best to explain why he’s her favourite writer of all time.

Some time last year I wrote to Steve B and asked if he was interested in publishing an interview I was planning to do with Mark Leidner. He wrote back, “Ha you and your unholy love and worship of that guy!”

Well, maybe. But what’s the fun in loving something if you can’t bore and alienate other people with it?

To be honest, most of the time I have no idea why Mark Leidner’s writing is so good. It’s like how leading scientists have never properly been able to explain the sunset. Last I heard it had something to do with chemtrails.

Advanced praise for books is a kind of arms race in which the adjectives keep getting bigger and bigger and eventually you start to feel like you didn’t bring enough guns to the party. But I don’t want to sound insincere. So I thought I’d say very simply what Mark Leidner’s writing means to me.

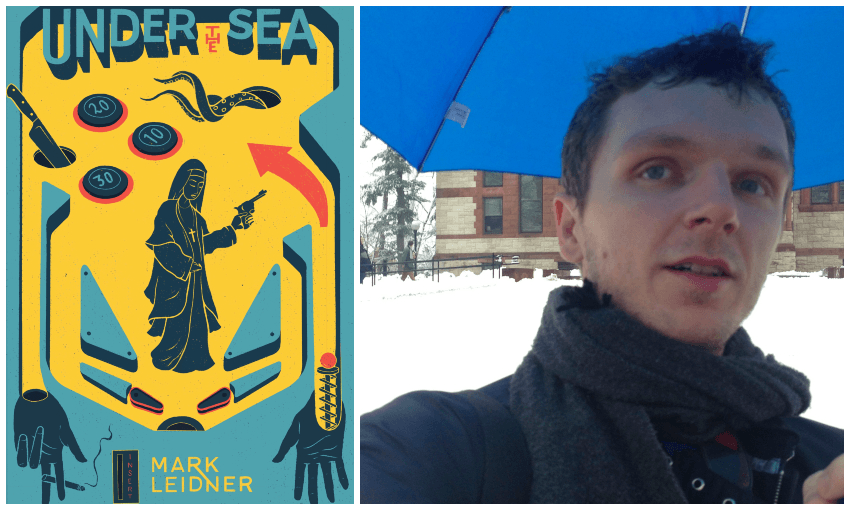

First, the facts. He did an MA at Iowa writers workshop. His first book was a collection of poetry called Beauty Was the Case they Gave Me published by Factory Hollow Press. He wrote a book of aphorisms called The Angel in the Dream of Our Hangover published by Sator Press and a chapbook called 21 Extremely Bad Breakups which won the Newfound Prose Prize and is included in his new short story collection Under The Sea published 2018 with Tyrant Books. He wrote the screenplay for a 2018 film called Empathy Inc and is currently working on a romantic comedy novel. His Twitter has its own unique place in the literary canon. His photography Tumblr is very good. So are his collages. You should stop reading briefly to watch this video from his YouTube. It’s not surprising that Leidner habitually switches form because his work often experiments with genre and stylistic constraint which he then effortlessly Houdinis out of.

How could you not love a writer who describes someone’s asshole as “a red wedding ring, never worn”? And how could you not want to read a poem called ‘Love in the Time of Whatever Disease This Is’ or ‘Little Children Riding Dogs’?

Mark Leidner was my favourite poet before I even knew who he was. The first poem I loved of his (still my favourite poem by anyone) was called the river and it was from a photocopied handout that had come unstapled. For a long time I assumed this poem had been written by someone else. The author I thought he was had some other, okay poems but nothing groundbreaking. And then the internet rose slowly over the horizon and there was light where there was once darkness.

Reading Mark Leidner’s writing changed my life. Maybe it’s embarrassing to say that, but it’s a cliche for a reason. How often does a piece of art internally warp you so much it messes with who you are on a cellular level? Why not say it if it’s true? When I first read Beauty is the Case They Gave Me I had that depersonalising shock you get where you relate to something so deeply you can’t believe it doesn’t already belong to you. It’s like when you stare at Julia Roberts’ face for so long you forget what you look like.

Reading Mark Leidner’s writing taught me how to write, and I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude. He is my favourite writer. His new collection of short stories Under The Sea is unbelievably good. The stories range from long realist pieces about teenagers trying to recover stolen drugs and a middle aged women having a meltdown in a coffee shop to a Chekhovian drama set in an ant colony and a kid writing his memoirs in the style of Philip Marlowe. I asked him some questions and he was nice enough to answer.

Hi Mark, how are you?

Grateful to be alive and talking with you, Hera.

Congratulations on your new book. I liked it very much. What was writing it like?

I’d written mostly poetry before, so the earliest stories in this book relied more on monologue, lists, and absurdity, which is similar to how I write poems. Later stories, however, relied more on plot, setting, and conflicts between characters. Overall, writing the book was like going through a metamorphosis in which I tried to get a handle on some of the conventions of fiction while coming from the conventions of poetry. I learned a lot, so it was fun and felt worthwhile.

You’ve written in lots of different mediums – poetry, aphorisms, short stories, tweets, screenplays, and I read somewhere you’re working on a novel. I know the question of what separates these different types of writing gets more and more boring and probably irrelevant every year. But it makes me feel relaxed too, because I don’t know how any person is capable of writing more than three poetry books in their life without getting bored. Was it a conscious choice to work across as many mediums as possible? Are there other formats you want to try?

By the time I’d published a couple poetry books, I’d invested so much of my self-esteem into writing poems that I became afraid to screw up. Writing in other genres helped me recover the feeling of freedom that comes when you have no expectations for success and your mental health is dependent on exploration rather than outcome. The novel I’m writing now is a rom-com, a genre I found that I was able to write in without fear of ruining anything, I think because, as a genre, it’s generally considered to be vapid and formulaic. A few other genres that seem equally unlikely to succeed (and thus which are appealing to me) include high fantasy, slasher, and underdog sports story.

My friend was talking about being interviewed and how everyone asks him about the humour in his poetry and stories, but they never ask him about the seriousness in them. Is this a dumb question to ask a funny person? What does the seriousness in your work mean to you?

I appreciate your friend’s discomfort with being unfairly reduced to a single identity or shtick. I wish we lived in a world where every writer’s and artist’s full complexity was always appreciated. Unfortunately, being reduced and misinterpreted is the natural tendency of the discourse, or so it seems to me. We don’t get to control how we are seen, only how we see. As soon as a piece is public, the right of interpretation transfers to others who can use it responsibly, beautifully, lazily, or callously. I doubt if it’s ever been different.

For me, seriousness is just a way to push a line of inquiry further in any piece of writing. I often begin with a frivolous or idiotic inquiry and then see where it leads, and it almost always leads somewhere serious. I’m not sure why. Maybe because everything is serious, even jokes and even dreams. As a person in real life, I’m pretty silly (often annoyingly so), but also I am pretty serious (also, often, annoyingly), so being both things (and hopefully other things) in writing is just an attempt to be true to the spectrum.

I liked the part in the beginning of Lost in Translation, where the narrator wonders if this is the moment their life finally changes genres. It’s something I think about a lot. The idea that you could be living one kind of life, thinking you were in a slacker comedy, and realizing at the end it was an espionage thriller all along.

I’ve had the same fantasy all my life. In a story, a character is constrained by the genre they’re in, and they can become extremely powerful or extremely impotent when they possess or are afflicted by “genre-awareness.” In life, we are constrained, empowered, or afflicted by knowledge of our own context in a similar way. The fantasy to change oneself by changing one’s context (or genre) is, I feel, primal. For better or worse, so is the desire to conform to one’s context and preserve an identity against forces eroding it. Both, I think, are universal and usually in some degree of conflict within every person

Shows and movies that offer a total genre switch are rare, but they do occur. A genre-switch mid-story, though, is playing with fire. Even if you do it well, you may still alienate all in the audience who like genre to stay in its lane. And if those are your most die-hard readers, viewers, or fans, disappointing them can be painful. If the execution is poor, however, all but the most avant-garde appreciators of convention-shredding will probably hate it. So, it’s perhaps tragic, but it at least makes some economic sense that most storytellers adhere rigidly to expectations of the genre they work in, if only to avoid making their perceived audiences furious.

All that being said, literature, and especially poetry, is like a primordial ooze where genre can change explosively into anything and out of anything else. Unlike in TV and movies, which are so expensive to create that such experiments are harder to justify, in poetry, and to a certain extent any type of literature, there is less risk since costs of production are so comparatively small. A miscalculation costs nothing but the writer’s time, and starting over is as easy as hitting delete. I think that’s why poetry and literature in general will always be a sanctuary for hideous, beautiful, and revolutionarily hybrid forms of meaning.

It seems to me that one of the hard things about writing short stories is that we’ve sort of been taught to read them as parables. I can’t help feeling when I’m reading short stories that there’s a lesson or a teaching I’m supposed to be extracting from them, even when that’s obviously not the author’s intention. How do you deal with that expectation as a writer. Do you think stories can teach you how to read them?

I think our brains continually search for lessons in any narrative. Of course, some narratives resist giving any lessons while others yield lessons too easily, or offer lessons that are simplistic or false. Either way, it’s one of my favorite things about us that we can’t help but to seek (or reject) meaning in every pattern or break in pattern we notice.

For me, part of the fun of writing stories is playing with this inherent lesson-seeking that readers bring to any text. Simply by raising the expectation of one lesson, you can invite the reader’s judgment faculty to participate in the meaning-making of the story. Later, you can fulfill that expectation with no surprises, or subvert it, complicate it, reverse it, or even undermine the notion that any lesson exists at all. For example, a lot of noir – on the opening page – illustrates the lesson that “people are corrupt and you shouldn’t trust them.” In many stories, this lesson goes on not just to be repeated in every scene, but exacerbated. This invites you to keep reading/viewing because you want to know how corrupt people can get – at least in the story – or what the consequences of that corruption might ultimately be.

But in a good noir – or any good story – the “lesson” on offer at the beginning is continually pushed past the threshold of expectation until we arrive at an unexpected lesson. For example, “Not only is the world corrupt, but the only way to restore justice in a corrupt world is to sacrifice love itself” or “The past is the monster that haunts the present forever – in every society.” So, I like stories that intrigue you with an apparent lesson only to take you on an unfolding path toward an increasingly sophisticated and surprising lesson. Again, the ultimate lesson may even be “there are no lessons, there is nothing to learn, stop seeking lessons in things” which is itself a powerful lesson. In good stories, the “lesson” is as dynamic and complex and ambiguous as we would expect any other element – like character or setting or style – to be. It’s the complexity or multiplicity or mixture of irresolution and resolution among a lesson or set of lessons in a story that keeps inviting us back into it to rediscover new ideas, new questions, new tiny mirrors of experience (which are new experiences themselves).

In this way, unlike the straightforward instructions you get in school or on the job or from your elders, literature can be a form of dynamic instruction that responds elastically to an individual’s private needs at the moment of encounter with the text. My favorite stories speak different truths depending on which questions I personally am ready to ask, and which answers I am ready to accept.

Do we have free will? Does it matter either way? I only ask because you namedrop fate and destiny so many times in this book.

For me, randomness, free will, and fate chase each other in a circle. They are fluid. At various times, one or the other seems to dominate. I relate to characters who worry about whether they have a choice or not in their identity-defining moments, and whether it matters – because I wonder that all the time in my own life. Imagine a character who must take on greater responsibility than they believe themselves capable. For some, the feeling that they are destined to succeed in that endeavor might give them the courage to step up. For others, the feeling that they are heroic if they choose to step up in a universe without any overarching order might instill in them the necessary courage. For a third type of character, the feeling that nothing matters at all – because everything is random – might allow them to say, “Fuck it. I might as well try because I have nothing to lose.” I have relied on all three of these attitudes at various moments when I was afraid. Having some appreciation for the possibility that fate may exist in some form and some appreciation for its inherent implausibility helps me be to be philosophically fluid – and therefore decisive – in a life seemingly full of real or imagined crises.

I like the Wheel of Fortune as a way to think about the continuum of destiny and randomness. One way I heard it explained once: we experience bad things as we ride the Wheel of Fortune down, then good things as we ride it back up on the other side, then bad again as we go down the first side again, then good again as we come back up the other side, over and over as the wheel spins until we have no more hours left. Every time you cross over the top of the wheel, you experience stunning grief, as all you’ve worked for is undone by bad luck, your own choices, or just the advance of time. At the bottom of the wheel, however, you have endured so much pain and suffering that when the wheel beings to turn upward again you have a chance to experience joy – first as humility, then as relief – as suffering climaxes and subsides as you start to rise. I think we are always somewhere on that wheel in our own minds, and so is every character. Obviously, some people spend more time on one side of the wheel than others, and too many don’t even get to go all the way around the wheel once. But thinking about the pattern of the wheel in my own life has been a useful way to remember that neither happiness nor suffering lasts, and the closer you get to the extreme of either, the closer you get to its eventual reversal.

You studied economics at university. What about economics most interests you? What is money? Is it bad for art?

In high school I had a great calculus teacher. Because of Mrs. Murphy, when I got to college, I found I could do econ problems easily, so I made it my major. Economics also seemed to be able to explain the mystery of human behavior using math, which felt like seeing the matrix. Up to that point, money, politics, war, and even love had seemed too complicated to ever understand. Through the lens of economics, however, anything seemed comprehendible – and even predictable. Not only that, economics spoke in a language that I believed was objective.

When I got to upper level econ courses, however, the math got too hard, and the questions being asked through it were so specialized that I had no emotional investment in them. I fled into English and writing at that point, where general inquiries like what is money? what is power? what is love? who are we? were more welcome, and the methodology for exploring those questions – stories, poems, words – although they were more biased, were far less arcane, far more robust, and had a much larger audience.

Because it is a medium, money is as arcane and slippery as whatever it mediates. For example, I used to think it was simply a vehicle for the exchange of value. Just like if you own a truck and use it to smuggle weapons for Nazis, you’re evil. But if you use the same truck to cart medical supplies for refugees, you’re good. The truck, like money, is morally neutral. This was how I thought of money for most of my life.

Then I read Debt: The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber, which opened me to a new perspective. Graeber argues that money is not neutral and is instead inherently corrosive regarding the implicit social bonds which function like money in pre-money societies and other sub-industrial units like families. For example, when most children turn 18, they aren’t suddenly given an itemized bill for all the food their parents provided them since birth. The 18-year-old is instead burdened with a more ambiguous moral obligation to be a part of its parents’ lives, or to carry on some aspect of family tradition – at least in most societies. To most people, presenting an 18-year-old with such a bill would be grotesque because it would transform a debt of gratitude that only that child could ever be bound by and which can never truly be paid back – with money – a commodity that could be paid back by anyone and even sold the way financial debt is sold from person to person in the modern economy—freeing the child from any moral obligation to their family.

Money, Graeber suggests, operates like that bill presented to that 18-year-old on all community relationships in the real world. While it appears to have no agenda, money strips effort of its specific cultural or interpersonal context and imbues it instead with an acultural, contextless evaluation. Looked at like this, the old Bible verse “The love of money is the root of all evil” starts to ring true. When people act in order to enrich themselves rather than to fulfill personal, familial, or cultural obligations to one another, they are much easier to dominate politically. In this way, merely introducing currency into a community can be an imperialist act.

Of course, my summary of Graeber is probably highly flawed – and we are ignoring the many benefits of money – but I’d seriously recommend the book to anyone curious about in a definition of money that complicates the usual “neutral medium of exchange” story.

Money then, I guess, must be negative for mainstream art, as it strips context—the real source of meaning—from everything it touches. (Or perhaps, if we wanted to be generous toward money, it replaces familial or communal contexts with national or global ones). Even if, however, we lived in a more money-dominated dystopia than the one in which we already live, I believe that someone somewhere would still be making art that is as good or better than anything that has ever been made before.

It might not be influential, and maybe it would have no audience beyond its maker, but it would exist in the same way that all the art made by all the people around the world that no one knows about still exists and has a meaning – in the making, to the maker, and, I would argue, to the universe – far beyond any potential market value. As individuals and as a species, art is how we fashion our mental reality, and until the robots are directly controlling all our dreams like in The Matrix, some art somewhere will be safe from the zombifying force of money.

One of my favourite stories is ‘Garbage’ where a woman in line at a Starbucks berates a couple of rude teenagers with a weirdly grandiose ‘This is Water’ David Foster Wallace speech. I love this story. It makes me feel like I’m in denial about something, but I don’t know what. Can you talk a little bit about it?

I know that story was inspired by an incident I witnessed, but it was so long ago that I no longer remember what’s real or made up in it. I also think the story is about how lonely a public place can be to the inner self of someone in emotional turmoil. I think we are all in denial about how much we yearn for the sort of closeness that requires giving up something of ourselves, and we opt instead for the illusory closeness of screens and pastries and coffee and commerce because it seems to cost so little. But it costs everything, makes us hate one another, and makes an emotional prison of convenience. I’m certainly guilty of denying how much it harms me and others.

Writing the story, I think I was trying to make use of some of those feelings. I wanted to write a character who was lonelier than anyone in a place where people seemed on the surface so happy and “normal,” and who, despite their loneliness, still tries to communicate through the fog of self-hate that loneliness causes.

What have you been reading or watching lately?

My favorite thing to read (and recommend) is Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels, about a private detective solving gruesome crimes in Nazi Germany. I’ve never read anything as dark and probing about the problem of evil that also shows the power and beauty of language in such an entertaining and accessible way. These books are brutal, though, and not for the faint of heart. Trigger warning times a billion. I’ve also been recently addicted to The Commonwealth Saga, a bewilderingly long and complicated space opera by Peter F. Hamilton. But if you’re into that sort of thing, it’s an endless buffet. There are so many characters and conversations in the novels of his that I’ve read that I still can’t believe how non-repetitive his prose is. Personally, I can’t seem to write one conversation without feeling like I’m overusing “says” and “looks” and “smiles” and “frowns” a thousand times, but Hamilton is endlessly creative in the nitty gritty of dialogue management, and I feel like I learn a lot from it.

Timothy Zahn’s Thrawn was maybe my favorite one-off novel last year, but it’s to be avoided if you dislike Star Wars. Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties was an awesome multi-genre story collection full of formal invention and the seamless interweaving of sci-fi and horror tropes with rich language and deeply felt character. Another book I loved was Kristin Iskandrian’s Motherest, a patiently observed novel about a girl who gets pregnant in college, from which I felt like I learned a lot as a writer. I tend to obsess over plot these days, but Motherest reminded me that the best plots are deeply understood characters simply doing what they do.

My favorite non-fiction I read this year was lazenby’s Infinity to Dine, a collection of searingly insightful and complicated poetic essays, and Claire Evans’ Broad Band, a heartfelt and entertaining history of women in technology. My favorite book of poetry was Alice Miller’s Nowhere Nearer for its buffet of perspectives, different types of poems, and brief but rich glimpses into modern history and the lyrical consciousness. Some of the above people are my friends, but I stand by the endorsements.

One of the things I really love about these stories is how much emotional intelligence the characters have. I’ve been reading a lot of contemporary fiction lately, and a lot of narrators have this weirdly stunted understanding of other characters’ motivations. I guess it’s kind of Shakespearean to have everyone misunderstand each other all the time, and useful for advancing plot. But the way you describe the relationships between the characters seemed very real to me. What do you think about when you’re trying to capture the relationship between two people on a page?

Someone once told me “Make every character as smart as possible.” I forgot who it was, and it took me a million years to even understand what that meant, but once I started trying to apply it, my stories took a leap forward. Another forward leap came when, after taking some acting classes and by trying to write a few movies, I realized that for any scene to be interesting, it has to have an interpersonal conflict, and each character must want something specific from the other, and for that conflict to be interesting, it must escalate while also having no predetermined conclusion. Only by putting all these pieces together – emotionally intelligent characters who are in a conflict with one another that escalates and has no foregone conclusion – do you have a recipe for compelling relationships. To me the best stories occur when everyone – protagonists, villains, even frame characters – are all extremely smart. Only then do the outcomes of their conflicts seem unpredictable and therefore verisimilitudinous.

Do you ever worry what writing does to your brain, long term?

One time I was complaining about how much money I waste by buying coffee at coffee shops instead of brewing it at home – $5 a day added up over a whole year is $1,825 – and my friend Rome was like, “Yeah, but that’s a small price to not go insane.”

I don’t think I’d go insane without writing, but I might be so bored or anxious that I did something much worse with my time just to use up the energy. If I found something else that felt more beneficial to my mental health and also offered the same sense of deep participation in the mysteries of reality, I would probably do that instead. I just haven’t found it yet, or I am too lazy to look very hard. Also, although no one can know what they would have become if certain things had not have happened, I do believe writing has helped change me for the better. Before I discovered it, I didn’t know what to do with myself and almost went to law school. As good as that might have probably been for my personal finances, I can’t see law transforming me in the same way writing has. Writing has given me a purpose and reconnected me with idealism. Through it I’ve met a world of inspiring and generous teachers, friends, and writers, living and dead, who by simultaneously challenging and believing in me, have made me less oafish and more thoughtful.

How do we live good lives and make good art?

Try to love yourself if you don’t. Try to love others more if you don’t do that. In both cases, try to let your love inflect your art at its deepest level. None of that is easy, so forgive yourself when you fail, and forgive others when they fail. Give everything to the effort, and try to let go of the outcome.

Under The Sea by Mark Leidner (Tyrant, $35) is available at Unity Books.